Discover the history and beauty of this heritage dessert.

History or legend ???

A little wonder born from the peasant trick.

Imagine the 16th century: no Netflix, no smartphones, but a much tasty invention - the Basque cake! Born in the rural kitchens of Labourd (Sukaldea) and Basse-Navarre (Eskaitzia), this delicious creation was originally a peasant genius: transforming simple ingredients into an extraordinary dessert.

Small fun detail: For a long time, this cake was a well -kept secret. In soule, they preferred the piñolets and the kruxpets. They only really discovered this treasure when he left family kitchens to become an artisanal star.

Warning: the history of this cake is a bit like a good novel. It's too easy to turn reality into a golden legend! Enthusiasts love to embellish the origin of local products, but the truth is often simpler and tastier. . On farms, families prepared this first ancestor of the cake with the most accessible ingredients: freshly ground "Arto Gorria" corn flour, wild honey from Erle Beltza (Important when you know the place of the bee in the Basque Country) , and lard to bind it all together, no eggs, too precious, they were used as currency to obtain salt, fabrics or tools from traveling merchants. This original cake was dry, dense, almost austere - like mountain life itself. For decades, the etxeko biskotxa remained like this, a simple companion on long winter evenings when families gathered around the hearth to listen to ancestral legends told by the elders. Its transformation into a filled pie was born, according to oral tradition, from a chance encounter. It is said that in 1580, a young shepherd named Mattin d'Itxassou, particularly curious and adventurous, accompanied a wool merchant to Bordeaux. There, he discovered for the first time French tarts filled with fruit and creams. Dazzled by this culinary revelation, he returned to the village with a revolutionary idea: to transform the dry etxeko biskotxa by adding a filling. Upon his return, Mattin experimented with his grandmother this new way of making their traditional cake. The dough was gradually enriched with eggs—now less rare—and butter, becoming more supple and generous. For the filling, they initially used what nature generously provided: wild sloes picked from the hedgerows, figs ripened in the summer sun, and sometimes cherries from the few cherry trees that thrived in the region. This was the birth of a new tradition. From farm to farm, each family adapted the recipe according to their own resources and tastes. The gâteau Basque became the very expression of the identity of the household that prepared it—etxeko biskotxa literally meaning "house cake." The major turning point in the history of this pastry, however, came in the 19th century, when Cambo-les-Bains began to attract a wealthy clientele who came to enjoy its thermal waters. It was in this context that the Hirigoyen sisters entered the legend of the gâteau Basque. These two enterprising women, Marianne and Catherine, ran a modest bakery in the heart of Cambo. Heirs to a family recipe passed down from generation to generation, they had the intuition that their version of the Basque cake could appeal to visitors in search of local specialties. The Hirigoyen sisters refined the ancestral recipe, standardizing its preparation and adding a touch of refinement that quickly won over the spa clientele. Their major innovation was to replace fresh fruit, available only seasonally, with a carefully prepared black cherry jam, thus making it possible to offer the cake all year round. Their shop quickly became a must-visit for spa guests, and the reputation of their cake soon extended beyond the borders of the Basque Country. The Hirigoyen sisters thus greatly contributed to transforming what was simply a family pastry shop into a true emblem of Basque gastronomy, known and recognized far beyond the mountains where it was born.

Local bakers and pastry chefs, smelling the opportunity, appropriated the peasant recipe to refine it. The jam replaced the fresh fruit, allowing the cake to be used all year round for enchanted spa guests. The last major metamorphosis of the Basque cake occurred much later, probably at the beginning of the 20th century, when the pastry chefs introduced pastry cream as an alternative garnish. This innovation experienced immediate success, now dividing aficionados from the Basque cake in two passionate camps: fans of jam and defenders of cream. Thus, which was once just a simple galette of corn and honey has become, over the centuries and innovations, one of the most famous and appreciated emblems of Basque gastronomy - a sweet witness that has always been able to marry tradition and innovation.

The importance of transmission

Between tradition and technique

I have often found myself faced with a delicate balance to preserve. On the one hand, these wonderful family Basque cakes, witnesses of a story transmitted from generation to generation. On the other, my rigorous pastry training where each gram counts. How to advise without hurting? How to bring my technical knowledge without offending these precious memories?

These family recipes deeply touch me. They talk to me about an era when you did not measure with scales of precision, but with the heart. A cup of "well-filled but not too" flour ", an old-fashioned spoon of sugar, that of grandmother", a pinch of salt "like that, you see, between the thumb and the index". Gestures that tell a story much more than they define quantities.

Faced with these testimonies, I feel like a guardian of two worlds. That of professional pastry where even salt is weighing to the nearest gram, where temperatures are checked and timed mixtures. And that of the family tradition, where we recognize that the dough is ready "when it makes this little noise under the fingers", where we know that the oven is at the right temperature "when the sheet of paper becomes golden in exactly thirty seconds". So I navigate with delicacy between these universes. I try to provide technical answers without ever questioning the validity of these ancestral methods. Because after all, these imperfect cakes according to professional standards are perfect in their imperfection. They carry in them the love and the memories of those who shaped them before.

I sometimes suggest light adaptations, I offer tips to understand why the dough reacts differently depending on the day. But I always take care to preserve the soul of these recipes, to respect these approximate measures which make all their singularity. Because basically, what makes a good Basque cake? Is it the scientific accuracy of the proportions or the emotion that submerges us when we find exactly the taste of our childhood? These meetings taught me humility. Pastry science is only one way among others to reach beauty. And these family recipes, with their imprecise measures and their well -kept secrets, have a magic that our precision scales will never be able to capture.

It is in this space of mutual respect that our most precious exchanges are woven, where tradition and technique meet without competing, enrich without distorting.

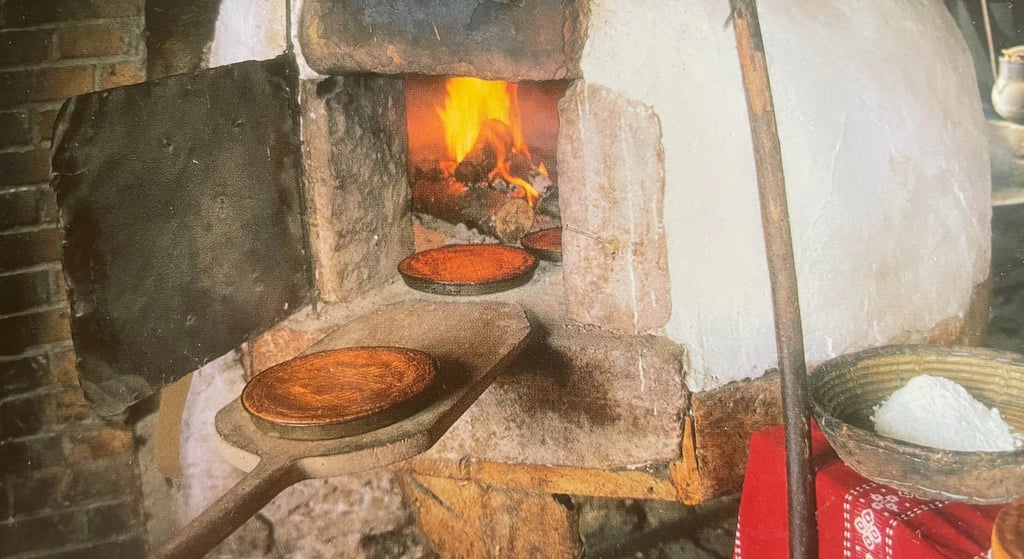

Oven from the Lapitzia farm in Sare

Did you know?

Despite its fame today, the Basque cake was not yet officially codified in 1843 . However, there were craft versions in the villages of Ustaritz, Cambo or Sare. In Pasaia, Hugo would probably have tasted a more rustic version, transmitted from generation to generation.

A culinary romance:

This jewel of French pastry deserves that it is dedicated to it a few lines imbued with romance and history. Born in the green valleys of the Basque Country, this cake is the child of a proud and authentic land. Its golden and slightly crispy crust hides a tender heart - sometimes with pastry cream flavored with vanilla and rum, sometimes with black cherries jam. This duality recalls the contrasting beauty of the Basque country itself, between tumultuous ocean and serene mountains. The legend says that it was in the 19th century, in the small town of Cambo-les-Bains, that a pastry chef named Marianne Hirigoyen would have perfected this recipe. His "Etxeko Bixkotxa" (house cake) has become the symbol of generous and sincere Basque hospitality. Unlike the Sologne Tatin pie which owes its birth to a happy accident, or to Paris-Brest created to celebrate a cycling race, more sober than the colorful Kouign-Amann Breton with caramelized butter . The Basque cake was born from a family tradition, transmitted from generation to generation. His Basque cross drawn on top is not only ornament - it is the seal of a powerful cultural identity. If we compare it to its regional cousins, it is noted its singularity: - more rustic than the delicate tropézian pie from Provence - more structured than the soft Breton Far with prunes - more dense than the light galette of Norman kings The Basque cake does not try to impress by its complexity, as could be an opera

Multilayer Iparisian. He seduces with his sincerity and generosity, like a conversation by the fire with a longtime friend. Over the centuries, he has remained faithful to himself, resistant to ephemeral pastry modes. Even today, in the Basque villages, it is tasted with a black coffee or a glass of patxaran, in a moment of simplicity that touches the sublime. The Basque cake reminds us that sometimes the most beautiful love stories are also the simplest - it only takes a little flour, butter, eggs and sugar, transformed by expert hands, to create a memory that persists long after the last crumb.

University study:

Saspiturry, Virginie. "From the domestic sphere to the market and industrial sphere: the plural trajectories of the Basque cake from the middle of the 19th century to the present day". Terroir products , edited by Corinne Marache and Philippe Meyzie, Universitaires François-Rabelais, 2015. Https://books.openedition.org/pufr/25080

Anecdotes and family testimonies:

The butter spots: Marie-Claire Etchegoyen, 58 years old

My Amatxi Miren had a small notebook with the blank waxed canvas cover. The yellowed pages were covered with its fine and neat writing, with spots of butter and flour which testified to its regular use. In this notebook was her recipe for the Basque cake, which she herself inherited from her mother. Every Sunday, she was preparing her cake by making me participate. "You see, Marie-Claire," she said to me, "the dough must be worked just what you need. Not too much, otherwise it becomes hard. Not too little, otherwise it crumbles." She never used a scale, but her hands seemed to know the proportions perfectly. "A handful of flour, a little salt - just enough to wake up the taste - and the cream, always prepared the day before so that it is very cold."

When Amatxi died, my mother inherited the notebook. And then one day, during a rushed move, the notebook disappeared. We looked everywhere, but he had evaporated, as if Amatxi's soul had decided to win with her. I tried to recreate the memory recipe, but there was always something missing. It was never exactly the same taste. My daughter tells me that my cake is delicious, but I know that he does not have this indefinable little note that that of Amatxi possessed. Maybe the secret was not only in the ingredients, but in these wrinkled hands that had prepared this cake thousands of times, in this kitchen where the smell of butter and vanilla floated.

The recipe found: Jean-Pierre Borda, 65 years old

For years after the death of my Amatxe Graxi, we thought that his Basque cake recipe was lost forever. She had never written anything, everything was in her head. "What is the point of noting?" she said. "My hands know the recipe". We all tried to reproduce it, my mother, my aunts, but no one really managed. This particular flavor was always missing, this inimitable texture.

And then, five years ago, when we emptied the family home in Espelette before selling it, I discovered an old mass book in an attic trunk. Between the yellowed pages, a small piece of paper fell. It was a recipe, written by the trembling hand of Amatxi, probably in his last years. She had finally decided to note it, as if she knew she should transmit it.

The most surprising was “sekretua” (the secret) that she had scribbled at the bottom of the page "Add a teaspoon of amber rum and a pinch of Espelette pepper in the pastry cream. Do not tell anyone."

I prepared the cake following its instructions to the letter. When I took the first bite, I closed my eyes and thought I felt its presence next to me. It was exactly that. I cried like a child. Today, I made copies of this recipe for all my children and grandchildren. But I made them promise never to share it outside the family. Some treasures must remain in the intimacy of households.

The inheritance disputed: Sophie Barnetche, 42 years old

In our family, the Basque cake was a source of discord for years. My grandmother had two daughters, my mother and aunt. Both claimed to have inherited "the real recipe".

My mother said that Amatxi had transmitted the recipe to her cream, the only authentic she said. My aunt, she, swore that Amatxi had entrusted her with the black cherries of Itxassou, saying that it was the one that her own mother was preparing. For years, family meals have been punctuated by this culinary rivalry. Each brought their cake, and we, the children, we were delighted doubly without daring to say which we prefer, for fear of triggering a new argument. It was only recently, by finding old photos, that I discovered the truth. On a yellowed image of the 1950s, we clearly saw Amatxi with two different cakes on the table: one with cream and one with cherries. She did them both, according to the seasons and the opportunities!

I showed the photo to my mother and aunt during the Christmas meal. There was a long silence, then they laughed. Since then, each year, we have been preparing the two versions and we raise our glasses in memory of Amatxi, which managed, even after his disappearance, to bring the family around his table.

The collective recipe book: Michel Pery, 70 years old

When my Amatxi died, panic seized the whole family. No one had thought of asking her for his Basque cake recipe. It was an institution, this cake. He appeared at each party, each baptism, at each marriage. And now we were likely not to taste it again. My sister Maïté then had an idea. She contacted all family members and close friends who had one day tasted this famous cake. "Write me your memories," she asked them. "What you remember with ingredients, Amatxi's gestures, smells, flavors."

The testimonies flocked. A cousin remembered that Amatxi was always grasping the zest of a lemon in the dough. An uncle was sure that she used half-salted butter and not soft butter. A neighbor had noticed that she added a tablespoon of corn flour in the pastry cream to stabilize it.

Little by little, fragment by fragment, we have reconstructed the recipe. Maïté has compiled everything in a beautiful book, with photos of Amatxi and everyone's testimonies. She made them copies for the whole family.

The first time we have tasted the reconstituted cake, we all had tears in the eyes. It was perhaps not exactly the same, but he brought in him the love and the memories of an entire family. And in a way, it was even more precious.

Reverse transmission: Lucie Deremboure, 35 years old

My Amatxi (grandmother) was a modern woman who never really liked cooking. When he died, we did not find any Basque cake recipe in his belongings, although we have been a Basque family for generations.

One day, chatting with my Aitatxi (grandfather), I learned that it was he who was preparing the Basque cake every Sunday! It was a secret between them: while my grandmother went to mass, he cooked. When the guests complimented "the delicious cake of Amatxi" (grandmother), they exchanged an accomplice look and kept secret.

My Aitaxi (grandfather) then transmitted his recipe to me, noted on a sheet he kept hidden between the pages of a Ramuntcho novel. He taught me his tips: a hint of orange blossom in the cream, a touch of cinnamon in the dough, and above all, let the dough rest one whole night before using it. Today, my husband is preparing the Basque cake at home, depending on my grandfather's recipe. And when our friends compliment me, I smile at thinking about my Amatxi and his well -kept secret.

Digital heritage: Thomas Pierre, 28 years old

I have never known my Basque Amatxi (great-grandmother), who died before my birth. But his cake has become a family legend. My mother was trying to reproduce it for special occasions, but she admitted that it was never quite like that of Amatxi Kattalin. Last year, by cleaning the attic, we discovered an old VHS cassette dating from the 80s. To our surprise, it was a recording of my great-grandmother preparing its famous cake! My grandfather had filmed him without his knowledge, knowing that his recipe was likely to get lost.

We had the cassette digitized immediately. The quality was not excellent, but we clearly saw his gestures, his way of kneading the dough, preparing the cream. We even heard his comments in Basque, which my great-aunt translated.

I watched this video tens of times, noting every detail. Then I tried to reproduce the cake. The result has moved the whole family. My great-aunt, in tears, said: "It's exactly like my mother's." Today, I put this video on an external hard drive and I made copies for the whole family. The idea that anatxi (grandmother) continues to send us his know-how, even after all these years, has something magical.

The recipe found in an old book:

Martine Goya, 62 years old

My Amatxi (grandmother) Jeanne was from Hasparren. When she died, I inherited her library, including an old Basque kitchen book from 1912. He was in poor condition, the yellowed pages and the ink sometimes erased.

By leafing through it, I found, slipped between two pages, a sheet covered with the writing of my amatxi. It was his Basque cake recipe, with personal annotations. "More vanilla than what they say", "butter always at room temperature", "do not too much cook, the cake must remain soft at heart".

What moved me was to discover that this recipe was actually an adaptation of that of the book, but that Amatxi (grandmother) had changed it over the years to perfect it. In the margin, she wrote: "My mother's recipe, improved for my family."

I had this precious book restored and I framed the handwritten recipe. She is hung in my kitchen, and each time I prepare this cake, I feel that three generations of women cook with me.

The well -kept secret, I met all these people who told me secrets here are their testimonies:

I met them all over the seasons, these guards of a family treasure. They came to see me at the museum during my workshops, the air sometimes concerned, sometimes curious. "The dough is too crumbly today," said one. "She sticks to the fingers, I don't understand," sighed the other.

Each time, it was different. One day too soft, another too brittle. The weather, the humidity of the air, the temperature of the kitchen ... so many variables which transform the experience into a daily challenge. These moments shared around the technique, small gestures, tours of hands transmitted from generation to generation ... This is where the magic operates. In these moments where we exchange, where we confide, where we seek together to understand why "today, it is not as usual".

Their eyes light up when they tell me the story of their family Basque cake. The voice of Amatxi (grandmother) which still resonates in their memories, the hands of mom who shape the dough with fascinating precision, the perfume that invades the house on celebration days. They entrust me with their difficulties, their successes, their emotions ... But never, to the big one, they reveal the recipe. This secret remains well kept, like an invaluable treasure which is only transmitted by blood or love.

This confidence they give me by sharing their experiences, their doubts and their questions touches me deeply. I then become a privileged witness to this living heritage, of this culture which is perpetuated in each Basque home with its variations, its nuances and its mysteries. What a wonder to see this heritage still so vibrant, so jealously protected and yet so generously shared in what is most essential: the love of know-how, the pride of an identity and the joy of transmitting.

In their testimonies is emerging not a frozen recipe, but the story of a people, a culture, a way of being in the world. The Basque cake is not just a pastry - it is a living heritage that is reinventing itself every day in the kitchens of the Basque Country.

Testimony of a family transmission

A small nugget

Tradition does not sell, it is transmitted.

To keep a tradition is not a business of trade. It is not a well -enlightened showcase, a marketing operation or a hazardous variation on a Sunday brunch slate. No. A tradition lives where it was born: in houses, in the heart of homes, in repeated gestures without ostentation, in the memory of a grandmother, in the smell that escapes from a familiar oven.

The Basque cake is the perfect example. He is one of the rare cakes that carry in him an entire land, an identity, a pride. And this identity, it is based on two pillars: pastry cream or black cherry jam. Nothing else. Everything else is only interpretation, gap, deviation. We will speak of "adaptation", of "creativity", but very often, these words are only apologies to justify the progressive abandonment of what makes sense. Because by dint of adaptations, revisits, we end up losing the essential. We no longer recognize the Basque cake, neither his taste, nor his soul.

It's a bit like building a magnificent Basque house, with its half -timbered half -timbered walls, its two -sided roofs ... and that we came to stick a modern aluminum pergola on the facade. Yes, it may seem practical, even attractive for some, but it destroys harmony, history, the beauty of the place. It is a wart on the face of time.

The Basque cake does not need to be reinvented. He needs to be respected. And this respect begins in homes, in villages, in the humble and faithful transmission of original recipes. Those who tell the truth of a people, not the air of time.

So no, it is not the trade that protects tradition. They are families. It is the hands that knead, the words that tell, the memories that bind. It is these moments that ensure that a tradition does not become a simple product. That she remains alive, sincere, rooted.

Is changing the recipe is betraying? Or is it bringing to life?

Between tradition and technique

I have often found myself faced with a delicate balance to preserve. On the one hand, these wonderful family Basque cakes, witnesses of a story transmitted from generation to generation. On the other, my rigorous pastry training where each gram counts. How to advise without hurting? How to bring my technical knowledge without offending these precious memories?

These family recipes deeply touch me. They talk to me about an era when you did not measure with scales of precision, but with the heart. A cup of "well-filled but not too" flour ", an old-fashioned spoon of sugar, that of grandmother", a pinch of salt "like that, you see, between the thumb and the index". Gestures that tell a story much more than they define quantities.

Faced with these testimonies, I feel like a guardian of two worlds. That of professional pastry where even salt is weighing to the nearest gram, where temperatures are checked and timed mixtures. And that of the family tradition, where we recognize that the dough is ready "when it makes this little noise under the fingers", where we know that the oven is at the right temperature "when the sheet of paper becomes golden in exactly thirty seconds". So I navigate with delicacy between these universes. I try to provide technical answers without ever questioning the validity of these ancestral methods. Because after all, these imperfect cakes according to professional standards are perfect in their imperfection. They carry in them the love and the memories of those who shaped them before.

I sometimes suggest light adaptations, I offer tips to understand why the dough reacts differently depending on the day. But I always take care to preserve the soul of these recipes, to respect these approximate measures which make all their singularity. Because basically, what makes a good Basque cake? Is it the scientific accuracy of the proportions or the emotion that submerges us when we find exactly the taste of our childhood? These meetings taught me humility. Pastry science is only one way among others to reach beauty. And these family recipes, with their imprecise measures and their well -kept secrets, have a magic that our precision scales will never be able to capture.

It is in this space of mutual respect that our most precious exchanges are woven, where tradition and technique meet without competing, enrich without distorting.

A symbol of cultural identity

The Basque cake is inseparable from the cultural identity of this region straddling France and Spain. Born in the 19th century in the (Sukaldea) family kitchens, it is above all a domestic creation, a family dessert. It was the Basque mothers and grandmothers who, with their skilful hands, shaped this sweetness for special occasions. The real essence of the Basque cake lies in this intimate transmission, from generation to generation, within homes.

Each family has its own version of the recipe, jealously guarded and transmitted orally. These family recipes, with their subtle variations, constitute the true richness of this culinary heritage - much more than the marketed versions that are found today in pastries. If its traditional recipe - a shortbread paste enveloping a garnish of pastry cream or black cherry jam - seems simple, it hides a complexity of flavors and a symbolic richness specific to family Basque gastronomy. The crossed patterns engraved on its golden surface are not only organization; They tell the attachment of the Basques to their land and their traditions.

An economic and tourist heritage

Today, the Basque cake goes far beyond the family setting to become a real economic asset. The pastries and bakeries of the Basque Country make it their flagship product, some dedicating themselves only to its manufacture. The creation in 1994 of the Basque cake museum in Sarer and the annual organization of the Basque cake festival in Cambo-les-Bains testify to its importance in the local economy and gastronomic tourism.

These events attract thousands of visitors each year, creating a vital economic ecosystem for many craftsmen, farmers and local traders. The Basque cake has become the ambassador of a territory, encouraging travelers to discover the region through its culinary heritage.

However, this growing marketing is not without danger. Unlike households where tradition is perpetuated in its purest form, commercial versions sometimes move away considerably from the original recipe. In a quest for profitability or marketing innovation, some professionals modify the proportions, replace lower quality ingredients or add elements foreign to tradition. However, it is family recipes, preserved in the intimacy of domestic kitchens, which constitute the real treasure to save.

The impact of a hypothetical disappearance

Imagine the disappearance of the Basque cake and its secular know-how confronts us with consequences that would greatly exceed the simple absence of pastry on our tables. This loss would have deep repercussions:

On authenticity and cultural identity

The standardization that would inevitably follow would erase what makes the Basque cake a unique product, anchored in its terroir. What was formerly the expression of a family tradition would become a generic product, devoid of its soul and its distinctive signature which today makes its value. The Basque Country would then lose a strong emblem of its identity.

On organoleptic quality

The craft techniques perfected on generations by Basque families allow to obtain this particular texture - neither too dry, nor too brittle - and this perfect marriage between the golden dough and the creamy garnish. These sensory qualities, impossible to reproduce industrially, would disappear with traditional know-how, leading to irremediable taste impoverishment.

On intangible cultural heritage

The Basque cake is not just a pastry - it is the expression of a culture, a family history and a strong local identity. His disappearance would represent a heritage loss comparable to that of a historic monument, erasing with him stories, gestures and rituals transmitted for generations.

On the local economy

The economic ecosystem that has developed around the Basque cake - pastry craftsmen, local producers of flour, butter and black cherries in Itxassou, museums, festivals and tourist circuits - would be seriously affected. Jobs would disappear and a significant part of the tourist attraction of the region would erase with it.

On biodiversity and the environment

The production of the real Basque cake is intimately linked to local varieties, in particular the black cherry of Itxassou for its jam variant. The abandonment of this know-how could accelerate the disappearance of these specific cultures, more standardizing agricultural practices and impoverishing local biodiversity.

On gastronomic innovation

Paradoxically, the loss of this traditional know-how would also limit future innovation. The ancestral techniques of the Basque cake have inspired many chiefs who reinterpret this pastry with creativity. Without this authentic basis, the source of inspiration would dry up.

On consumer perception

Over time, consumers would get used to standardized versions of the Basque cake and lose the taste memory of the authentic product, creating a vicious circle of qualitative impoverishment. This phenomenon is already observable in certain regions where industrial imitations have taken precedence over the craft versions.

These losses would be particularly marked in the current context of globalization and food industrialization, where the transmission of traditional know-how is already threatened by the standardization of production methods and the evolution of lifestyles. The Basque cake could thus join the long list of regional specialties whose authenticity has diluted over time, until only the shadow of what once made their greatness.

Preserve the inheritance of the Basque cake

Faced with these threats, the real safeguarding of this heritage is not played out in the laboratories of professional pastry chefs, but at the very heart of Basque households. It is in the family transmission, from mother to daughter, from grandmother to little child, that the hope of authentic perpetuation of this know-how resides. The precise gestures to knead the dough, the exact time of rest, the ideal temperature of the traditional oven - so many subtleties that are not learned in books but by observation and practice within the family cell.

Some Basque families faithfully continue this transmission, organizing dedicated days where several generations meet to prepare the cake together according to the ancestral recipe. These privileged moments constitute much more than a simple pastry lesson-they are rituals of cultural transmission where the Basque identity itself is perpetuated.

Initiatives such as intergenerational culinary workshops in the villages or the collection of testimonials from the elderly holders of authentic family revenues contribute to this safeguard. The association of friends of the Basque cake, while working for the official recognition of this heritage, insists on the importance of these domestic traditions in the face of commercial excesses.

The real preservation of the Basque cake therefore requires a valuation of family practices, far from commercial adaptations sometimes imposed by economic constraints. It is by maintaining the flame of this tradition in the homes that the Basque cake will retain its authenticity and will continue to embody the soul of a territory and a people proud of its roots.

The Basque cake reminds us that gastronomy is much more than a matter of taste - it is a reflection of a cultural identity, a collective history and a particular relationship to the world. Its preservation is an issue that concerns us all, temporary guards of a millennial heritage that we must transmit to future generations.

Gastronomic tourism in which the Basque cake is paid for a beautiful slice:

Gastronomic tourism in the Basque Country: a unique sensory journey

Gastronomy has become one of the most powerful motivations to choose a travel destination. Beyond monuments and landscapes, it is through the plate that we really discover the soul of a place. The Basque Country, with Donostia, Bilbao, Logrono, Pampelune, St Jean Port, Bayonne, Espelette, St Jean de Luz as a culinary jewel, are the perfect illustration.

Donostia: the gastronomic capital par excellence

Nestled in the southern Basque Country, Donostia (San Sebastián) is a real revelation for the taste buds. This coastal city concentrates a large number of Michelin stars per inhabitant, but its true magic lies in its "pintxos" - these delicious bites which transform each bar of the old town into a gastronomic temple.

A typical evening in Donostia takes you from bar to bar in the districts where each establishment offers its specialty: here a gilda (pepper, anchovies and olive), there a cheek of ox simmered with red wine, elsewhere a tortilla with melting cod. This tradition of "txikiteo" or Poteo (bars tour) in Cuadrilla makes you discover not only incredible flavors but also the art of Basque.

Starch restaurants like Arzak, Akelarre, Mugaritz, Roget, Béchade, Roses and so many others reinvent traditional Basque cuisine with creativity, but remain deeply rooted in their terroir.

The Basque Country: a gastronomic territory without borders

The Basque Country is not limited to Donostia. This region straddling France and Spain offers an exceptional culinary diversity which follows the topography of the territory, from the ocean to the mountains.

South Hegoalde side

Bilbao, beyond its famous Guggenheim museum, offers a vibrant culinary scene. Casco Viejo pintxos (old district) bars compete in ingenuity, while restaurants like Azurmendi or etxebarri (near Durango) raise the local product to the rank of art.

The region of Getaria (El Cano) and Hondarribia (large floor) is renowned for its fresh fish grills (notably the turbot) cooked outdoors on barbecues visible from the street. The Txakoli vineyards, this slightly sparkling white wine punctuate the green hills with a view of the ocean.

In lands, Rioja Alavesa offers a spectacular wines between avant-garde architecture and secular traditions.

North side Iparralde

The Basque Country on the French side is not to be outdone with cities like Bayonne, the capital of ham and chocolate, where craft workshops perpetuate an ancestral know-how. Saint-Jean-de-Luz and Biarritz offer colorful markets where Espelette peppers rub shoulders with sheep's and fresh mountain and fresh fish cheeses from our Cotiers fishermen.

In the villages of the hinterland like Espelette, Sare, Ainhoa, Garazi, the Aldudes valley where we find magnificent tables, the farms-inns also offer rustic and generous cuisine: veal axoa, trout, milk lamb, piperade, or the famous basque cake .

You can also learn French with AI by making the Basque cake

When AI seizes the Basque cake

The industrialization of the Basque cake (1980 to today): a gourmet revolution

The industrialization of a traditional dessert

The modern story of the Basque cake is that of a spectacular transformation. From the 1980s, this traditional pastry gradually left the craft and domestic sphere to conquer the stalls of supermarkets and tables in all of France, not always the best images.

Boncolac , established in Bonloc in the Basque Country, was the pioneer of this industrialization. Specialist in frozen pastries since 1955, the company has taken the opportunity to develop a range of regional specialties including the Basque cake. The success was such that other companies quickly followed suit:

*Miguelgory, in Saint-Pée-sur-Nivelle specialized in the production of Basque cakes

*Basque fisheries, initially dedicated to fish preserves, diversified their activity towards this emblematic pastry

*Jock, a Bordeaux company created in 1938, pushed industrialization to the extreme in 2006 with a Basque powder cake, radically simplifying its preparation.

* And many others not always in the Basque and South West Country.

Handicrafts to industrial production.

Industrialization has posed real technical challenges. Companies had to rethink the mechanical manufacturing process by trying to maintain the essential qualities of the product while optimizing profitability.

Distribution has also been transformed: formerly confined to a local scale, this pastry is now present on the shelves of supermarkets on a national scale, even if its market heart remains the southwest of France.

Local marketing

Large areas have played a crucial role in this massive diffusion. For the past twenty years, faced with growing demand for authentic and "terroir" products, supermarkets have created specific ranges, which notably offer a Basque cake because it is cherry because of conservation for the cream.

The packaging skillfully exploits the Basque cultural symbols: the Basque cross (Lauburu), the flag (Ikuriña), a pediment, a house and the traditional red and green colors. This marketing strategy transforms the cake into a Basque culture ambassador on the shelves of supermarkets.

A heritage between tradition and innovation

Paradoxically, this commercial success has generated a certain disaffection of the premises, which sometimes consider the Basque cake as a product which no longer corresponds, "too touristy". To counter this trend, initiatives have emerged to revalue this emblematic pastry:

- Creation of a museum in Sare dedicated to the Basque cake

- Organization of an annual celebration in Cambo les Bains celebrating this pastry tradition

- Training of an Authentic Basque Cake Defense Association in Bayonne.

Between tradition and innovation, the Basque cake continues to evolve. If some actors seek to preserve ancestral recipes, others turn to creation, such as ice cake or savory versions.

Today, this pastry represents much more than a simple dessert: it symbolizes the delicate balance between culinary heritage, regional economic development and gastronomic innovation.

Salted version by Cedric Bechade

(sheep cheese, espelette pepper)

When an industrialist like Alsa does

His Basque Powder Cake:

https://www.alsa.fr/les-idees-recettes/toutes-les-recettes/recette-du-gateau-buqueque-du-patissier/

The 1976 egg strike: when the Basque cake almost disappears

the context: an unprecedented avian crisis.

In February 1976, an epizootic from Newcastle (avian viral disease) massively hit French farms. The government orders the preventive slaughter of millions of poultry. Simultaneously, breeders go on strike to protest against the insufficiency of the compensation promised by the State.

The duration: 11 weeks of agony

from February 15 to May 2, 1976, or 11 interminable weeks, France is practically without eggs. Stocks are exhausted in one week, emergency imports from Belgium and Germany are derisory in the face of demand.

The impact on Basque pastry

in the Basque Country, the disaster is total. The pastry chefs, accustomed to using 15 to 20 eggs per day for their Basque cakes, find themselves helpless. Jean Etchegaray, from the eponymous pastry to Saint-Jean-de-Luz testified: "In March, I paid 12 francs the dozen eggs on the black market, 10 times the normal price! Impossible to pass on my customers."

Desperate solutions

substitution eggs:

- Cane eggs : Some pastry chefs turn to duck breeders. Problem: pronounced taste of water game, more oily texture, poorly appetizing orange color

- goose eggs : too large, too rich, they completely unbalance traditional recipes

- quail eggs : expensive solution (you needed 4 quail eggs for a chicken egg) and tedious to chip.

The unhappy experience of Pantxo Idiart (Cambo-les-Bains)

Pantxo Idiart tries the experience of cane eggs in April 1976. He said: "I bought 5 dozen cane eggs to a breeder of Sare. The first batch of Basque cakes had a taste ... of pond! My regular customers believed that I had lost my hand.

Economic consequences

- temporary closures : 40% of Basque pastries close their doors between March and April

- Forced retraining : some turn to Easter chocolates (without eggs) or macaroons

- Debt : Egg purchases at the black market ruin several small businesses

innovation born of necessity

This crisis pushes certain pastry chefs to experiment:

- Vegan versions before the hour : use of apples. MOULUE LINE seeds

- Recovery techniques : drastic saving of yolks and white, reuse of crushed shells as calcium for surviving hens

The return to normal: May 1976

When eggs become available in early May, it is euphoria. Maite Harriague, from Bayonne, remembers: "On May 3, I made 50 Basque cakes at once! My clients were lining up as for the bread during the war."

Sustainable sequelae

- Professional trauma : a generation of pastry chefs keeps a panic fear of supply breaks

- Preventive storage : many install freezers to store beaten eggs

- Diversification of suppliers : end of exclusivity with a single local breeder

The heritage of the crisis

forge this period forge unprecedented professional solidarity. Basque pastry chefs created in 1977 a group purchasing cooperative to never relive this situation again. They also establish sustainable partnerships with local breeders, guaranteeing a priority supply in the event of a crisis.

Paradoxically, this strike of eggs strengthens the identity of the traditional Basque cake: after having tasted catastrophic substitutes, consumers and professionals appreciate even more the authenticity of the real recipe for farm eggs.

Adaptations of the Basque cake: Allergies and diabetes challenges

The gluten -free challenges

The basic problem

The Gluten of the wheat gives the Basque dough its characteristic texture: firm but melting, which stands without crumbling. Without him, it is a delicate balance to recreate.

Solutions tested by professionals

mix alternative flour:

-

Rice flour (40%) + buckwheat flour (30%) + cornstarch (30%) - Advantage: neutral taste, close texture

: trend

in crumbling, requires more fat

- almond flour (50%) + chestnut flour (25%) + potato starch (25%) Gustive, good resistance - Disadvantage: high cost, pronounced taste that masks traditional flavors

Lieux agents :

-

xanthan gum (1 teaspoon for 200g of flour): effective but risk of "rubbery" texture if overdose -

blond psyllium

:

Better texture but absorption of unpredictable water - Moutle flax seeds : natural solution but modifies The failed experience of pastry andxe (Bayonne, 2019):

attempt with 100% coconut flour: compact result as concrete, exclusively tropical taste that kills the Basque identity.

Lactose -free/vegan adaptations

The butter challenge

represents 30% of the weight of the dough and gives its particular taste. Replace it without distorting the essence of the cake is a feat.

Alternatives Tested :

specialized plant butter:

-

cocoa butter + coconut oil (50/50 ratio) - Advantage: similar texture, cooking outfit

- Disadvantage: residual chocolate taste, hardness too cold

-

high -end vegan margarine - Advance: Behavior of butter -

Disadvantage

: artificial taste, prohibitive

oleaginous puree : Creamy but too marked taste -

cashew puree : more neutral but completely changes the structure replacing the eggs:

each egg in the traditional recipe has a role: link, lifting, gilding.

Solutions by function:

-

For the connection : aquafaba (chickpea juice) - 3 tablespoons = 1 egg -

for lifting : bicarbonate + apple vinegar -

for gilding : vegetable milk + agave syrup + curcuma (for color) documented disaster:

a gourmet restaurant by biarritz (2020) Tent a 100% vegan version with oil with oil with oil with oil with oil with oil Olive Extra-Virgin. Result: a cake with a taste of tapenade, grainy texture, customers poisoned by bitterness.

The diabetic challenge

replace sugar: Mission Impossible?

Sugar is not used to sweeten: it gives the texture, participates in the gilding, balances acidity. Remove it upsets all the chemistry from pastry.

Edulcoating tested:

erythritol :

- Advantage: Neutral taste, zero glycemic index

- Disadvantage: Crystallize in cooling, refreshing effect in the mouth, cost 8 times higher than Stevia sugar

:

-

Advantage: very sweet, natural

- Disadvantage: residual bitterness, impossible to reproduce volumes (1g of Stevia replaces 200g of sugar)

Xylitol: Sugar - Disadvantage: Toxic for animals, laxative effect at high doses

Adaptations of pastry cream

The traditional cream contains 150g of sugar for 500ml of milk. The diabetic version becomes a headache.

Professional attempts:

-

Cream with apple compote without sugar : grainy texture, bland taste -

agave syrup cream : too liquid consistency, fast fermentation -

dates puree : brown color, dominant datte taste and failure innovations:

Spectacular

partial successes

The vegetable version, gluten-free, lactose and organic Marlene Gioia (Gioia)

Gluten-free of the Maison Pariès (Biarritz) 18 months of tests, they develop a mixture of rice/almond/arrow-root flour which reproduces 80% of the original texture.

Secret :

Double cooking at reduced temperature.

Diabetic adaptation of the Arbeaitz chef:

Use of soluble fibers (inulin) to recreate the texture, wrapped in Monk Fruit. Result: acceptable but requires an education of the palace.

Memorable disasters:

the incident of Lupine flour (2021):

a pastry chef from Saint-Palais tries Lupine flour for his protein wealth. Problem: 12% of the population is allergic to Lupine. Two hospitalizations for anaphylactic shocks.

The fermented Aquafaba fiasco :

attempt to raise the dough with fermented aquafaba. Result: Avant beer taste, spongy texture, disgusted customers.

Hybrid solutions and compromises:

The "gradual reduction

rather than total substitutions approach, some professionals opt for progressive reductions:

- 30% decrease in compensated sugar by spices (bourbon vanilla, orange blossom)

- partial replacement of butter (70% butter + 30% hazelnut oil)

- Adding soluble fibers to compensate for

" tolerance "versions:

for light intolerances:

-

Reduced lactose : clarified butter + lactic ferments -

Reduced gluten : old wheat mixture (fattening) + buckwheat -

reduced sugar : naturally sweet fruit (banana, apple) In addition adaptation and tolerances:

emerging technologies

-

3D food printing

you

recreate complex textures - controlled fermentation : development of natural flavors without additives - The properties of the ingredients The challenge :

the question remains: how far can we modify the Basque cake before it loses its soul? Some purists prefer

to

create

new pastries rather than distorting the ancestral recipe . Technical constraints of these adaptations 4.

Innovate in the presentation to compensate for the taste limits 5.

Maintain the friendly spirit of the Basque cake even if the recipe changes the adaptation of the Basque cake to modern constraints reveals the limits of our techniques as much as the unexpected richness of the traditional recipe.

A vegan basque cake

The Rugby gourmet parenthesis The Basque cake is a bit like the XV of France! Everyone has their opinion on it, everyone (is coach) thinks of holding the winning recipe . In the bistros and cafes of the Basque Country to the Parisian tables, the "pastry selectors" are not lacking. Everyone goes with their expertise: "No, but the real tradition requires less sugar!" Or "It's the cream that does everything, let's see!"

And then there are Sunday consumptions who comment on each bite as we would analyze a melee. Here they are discharging on the texture, cooking, balance of flavors ... while they still confuse Sara (Sare) and Garazi (Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port)!

As for professional pastry chefs, some resemble these players who proudly sing the Basque hymn without understanding a traitor word of what they sing. They master the technical gestures, but have they really seized the soul of this centenary dessert?

So the next time you bite into this sweet ball, ask yourself: are you a simple supporter or a real connoisseur of this gourmet match that has been played for generation S?

Teamgâteaubasque

Contact us

For any questions, do not hesitate to contact us directly.

Discover the authenticity of the Basque cake.

Gourmet tradition and heritage

+33 6 08 48 09 85

© 2025. All Rights Reserved.