Stories, legends and anecdotes !!!!

Long ignored, little known, the Basque cake did not have the place it deserved in the pantheon of French gastronomy. Our museum was born from this conviction: to have this culinary treasure recognized, to take it out of the shadow of regional desserts to give it the light it deserves. Each visitor, each story, each plot of our exhibition tells not only a story of sugar and tradition, but also legitimate recognition.

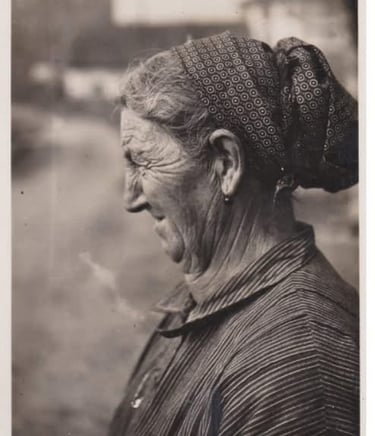

Amatxe holds the recipe

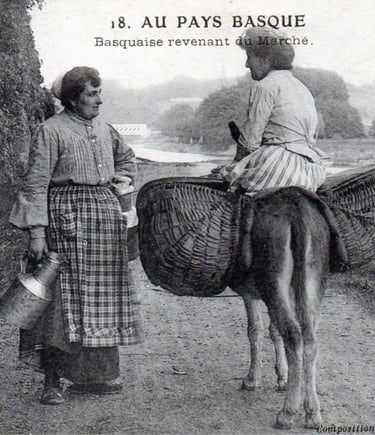

So made this market

All sold this morning that

If Cambo-les-Bains has brilliantly contributed to the fame of this specialty, it is important to recall, in a spirit of mutual sharing and recognition, that the Basque cake is the expression of a tradition common to the whole of the Basque country. Each village, each family itself, has developed over the generations its own interpretation of this emblematic recipe, thus creating a rich mosaic of flavors and know-how which testifies to the cultural diversity of our territory. The beauty of this dessert also lies in its deep origin in the Basque daily life. Far from being a pairing pastry reserved for special occasions, Etxeko Biskotxa (the house cake) traditionally found its place on the family table on Sunday, after the meal. This privileged moment marked the weekend, when the reunited family savor this simple but precious pleasure, carefully prepared by the expert hands of Etxkoandere (the mistress of the house). This family and Sunday dimension of the Basque cake reminds us that before being a marketed and celebrated product, it is first of all an expression of the hospitality and the sweetness of the Basque hearth, a tradition transmitted from generation to generation in the intimacy of family kitchens. It is this collective heritage, this culinary wisdom shared between all the provinces of the Basque Country, that we have today the privilege of discovering the world.

History or gourmet chronicle.

The geography of a cake:

When the identity can be enjoyed

Behind each Basque cake hides much more than a simple recipe: it is a territory, a story, a silent battle of memories and borders. For some actors in the Basque Country, this dessert is not just a sweet dish, it is a culinary manifesto whose borders are as precious as the ingredients that compose it.

Each crumb tells a part of the story, each flavor draws the contours of an identity. The geographic origin of this cake is not a simple detail: it is a cultural issue, a story of pride and belonging that is played in the hands of the craftsmen and the guardians of the tradition.

What if we had found a cake before the Basque cake!!!!!!!!!

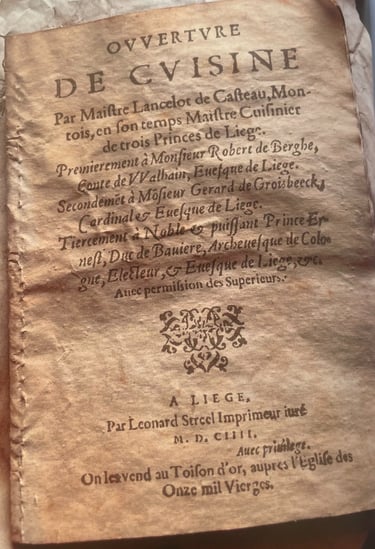

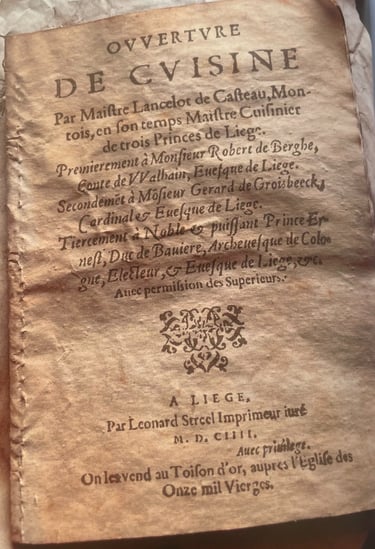

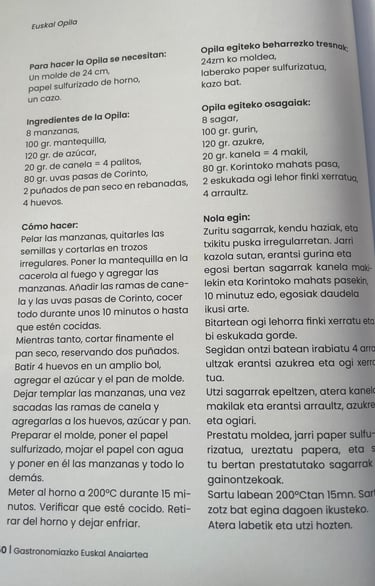

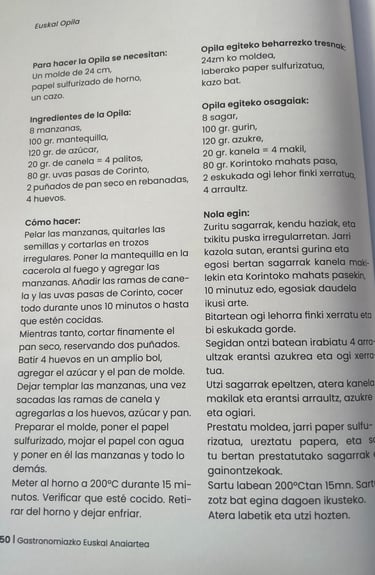

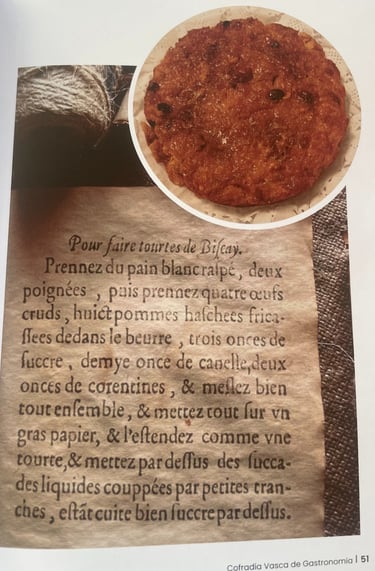

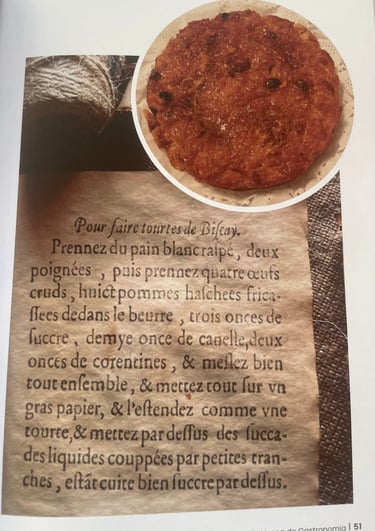

It was while leafing through an old culinary book kept in Liège, Belgium, that this recipe resurfaced. It once appeared in the library of the Cardinal of Liège and was written by Lancelot de Casteau , master chef to the prince-bishops of the city. Published in 1604 , this collection bears witness to refined gastronomic know-how, at the crossroads of medieval traditions and the beginnings of modern cuisine.

Some researchers see it as one of the oldest testimonies of a cake related to the Basque cake , with which it shares the structure and spirit, although it clearly predates . By its composition and symbolism, this preparation also evokes the Euskal Opila , a ritual cake always offered during festivals and family ceremonies in the southern Basque Country (Ego-Alde) .

Thus, between the pages of a 17th century Liège book, one of the forgotten roots of the Basque cake seems to emerge, in its own way.

The Biscay Pie

The geographic origin of the cake is an important issue for certain Basque actors.

The geography of a cake: when identity can be enjoyed

Behind each Basque cake hides much more than a simple recipe: it is a territory, a story, a silent battle of memories and borders. For some actors in the Basque Country, this dessert is not just a sweet dish, it is a culinary manifesto whose borders are as precious as the ingredients that compose it.

Each crumb tells a part of the story, each flavor draws the contours of an identity. The geographic origin of this cake is not a simple detail: it is a cultural issue, a story of pride and belonging that is played in the hands of the craftsmen and the guardians of the tradition.

Here the story finished and begins the legend !!!!!

A little wonder born from the peasant trick

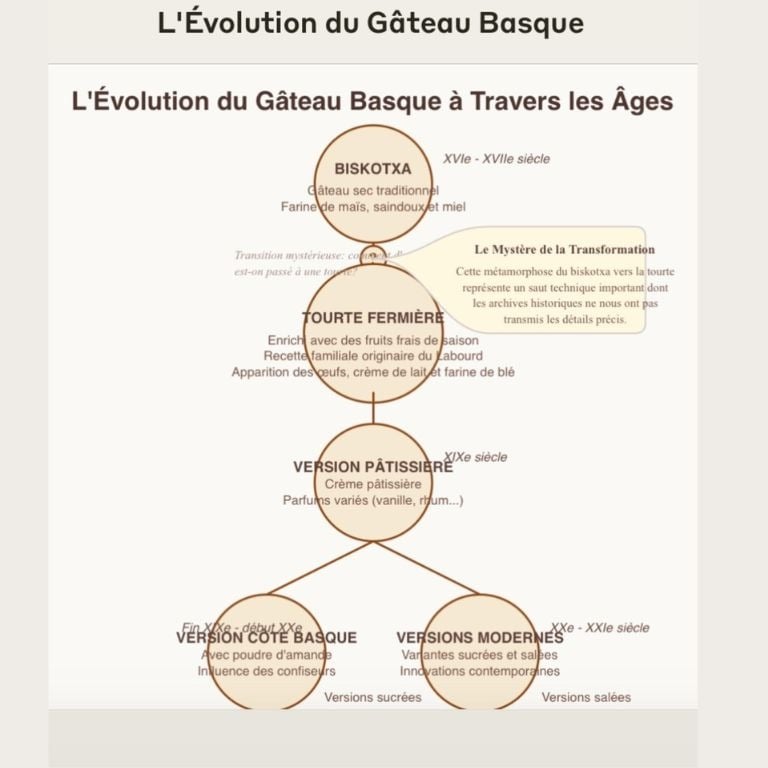

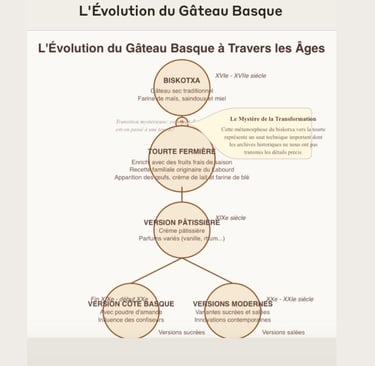

Imagine the 16th century: no Netflix, no smartphones, but a much tasty invention - the Basque cake! Born in the rural kitchens of Labourd (Sukaldea) and Basse-Navarre (Eskaitzia), this delicious creation was originally a stroke of peasant genius: transforming simple ingredients into an extraordinary dessert.

Small fun detail: For a long time, this cake was a well -kept secret. In soule, they preferred the piñolets and the kruxpets. They only really discovered this treasure when he left family kitchens to become an artisanal star.

Warning: the history of this cake is a bit like a good novel. It's too easy to turn reality into a golden legend! Enthusiasts love to embellish the origin of local products, but the truth is often simpler and tastier. . On farms, families prepared this first ancestor of the cake with the most accessible ingredients: freshly ground "Arto Gorria" corn flour, Erle Beltza honey (Important when you know the place of the bee in the Basque Country) , and lard to bind it all together, no eggs, too precious, they served as currency to obtain salt, fabrics or tools from traveling merchants. This original cake was dry, dense, almost austere - like mountain life itself. For decades, the etxeko biskotxa remained like this, a simple companion on long winter evenings when families gathered around the hearth to listen to ancestral legends told by the elders. Its transformation into a filled pie was born, according to oral tradition, from a chance encounter. It is said that in 1580, a young shepherd named Mattin d'Itxassou, particularly curious and adventurous, accompanied a wool merchant to Bordeaux. There, he discovered for the first time French tarts filled with fruit and creams. Dazzled by this culinary revelation, he returned to the village with a revolutionary idea: to transform the dry etxeko biskotxa by adding a filling. Upon his return, Mattin experimented with his grandmother this new way of making their traditional cake. The dough was gradually enriched with eggs—now less rare—and butter, becoming more supple and generous. For the filling, they initially used what nature generously provided: wild sloes picked from the hedgerows, figs ripened in the summer sun, and sometimes cherries from the few cherry trees that thrived in the region. This was the birth of a new tradition. From farm to farm, each family adapted the recipe according to their own resources and tastes. The gâteau Basque became the very expression of the identity of the household that prepared it—etxeko biskotxa literally meaning "house cake." The major turning point in the history of this pastry, however, came in the 19th century, when Cambo-les-Bains began to attract a wealthy clientele who came to enjoy its thermal waters. It was in this context that the Hirigoyen sisters entered the legend of the gâteau Basque. These two enterprising women, Marianne and Catherine, ran a modest bakery in the heart of Cambo. Heirs to a family recipe passed down from generation to generation, they had the intuition that their version of the Basque cake could appeal to visitors in search of local specialties. The Hirigoyen sisters refined the ancestral recipe, standardizing its preparation and adding a touch of refinement that quickly won over the spa clientele. Their major innovation was to replace fresh fruit, available only seasonally, with a carefully prepared black cherry jam, thus making it possible to offer the cake all year round. Their shop quickly became a must-visit for spa guests, and the reputation of their cake soon extended beyond the borders of the Basque Country. The Hirigoyen sisters thus greatly contributed to transforming what was simply a family pastry shop into a true emblem of Basque gastronomy, known and recognized far beyond the mountains where it was born.

Local bakers and pastry chefs, smelling the opportunity, appropriated the peasant recipe to refine it. The jam replaced the fresh fruit, allowing the cake to be used all year round for enchanted spa guests. The last major metamorphosis of the Basque cake occurred much later, probably at the beginning of the 20th century, when the pastry chefs introduced pastry cream as an alternative garnish. This innovation experienced immediate success, now dividing aficionados from the Basque cake in two passionate camps: fans of jam and defenders of cream. Thus, which was once just a simple galette of corn and honey has become, over the centuries and innovations, one of the most famous and appreciated emblems of Basque gastronomy - a sweet witness that has always been able to marry tradition and innovation.

In the Basque Country , Erle Beltza the bee also played an important role. She is addressed as "you" (zu in Basque ). When she is asked to come and settle in a new hive prepared for her, she is told aniere ederra

"pretty lady".

And the pastry cream in all of that would you tell me !!!!!

It is a French invention whose precise origin is difficult to determine with certainty. It is generally attributed to the cook François Massialot, who described it in his work "Le Cuisinier Royal et Bourgeois" published in 1691.

Massialot has a recipe for thick cream made from milk, eggs, sugar and flour, flavored with vanilla or lemon, which essentially corresponds to the pastry cream that we know today.

However, similar preparations probably existed before this formal documentation. Pastry cream is part of the gradual evolution of French pastry which developed considerably in the 17th and 18th centuries. This cream has become a fundamental element of French and international pastry, serving as a basis or garnish for many creations such as lightning, mille-feuilles, fruit pies and many other desserts.

The biggest names that have advanced French gastronomy from the 18th to 19th centuries, allowed significant advances in techniques.

Brillat Savarin in his famous book "Physiology of taste".

Marie-Antoine dit Antonin Carême and her superb book "The first of the chefs" with 100 recipes from the Maestro.

And Auguste Escoffier who revolutionized French cuisine and cuisine in general. It bible still tears up with the youngest "the culinary guide".

The Jean-Baptiste Etcheverry affair, the pastry spy of Ciboure (1943-1944)

Jean-Baptiste, nicknamed "Pantxoa", held family pastry against the port of Ciboure. Resistant in the "comet" network, he had found an ingenious system: slide coded messages in his Basque cakes by replacing part of the cream with fine papers rolled in beeswax.

The perfect system

The cakes were delivered to specific "customers" - in reality liaison agents. The code was simple:

- Normal grid = message inside

- Grock with diagonal scratch = no message

- Double gilding = urgent message

The fatal blunder of November 23, 1943

That day, Pantxoa is preparing two lots: "normal" cakes for the Germans of the Fort de Socoa (usual order on Thursday), and "coded" cakes for the network. In its precipitation - Aerial alert - it mixes controls.

The German -speaking miracle

The messages contained information on troop movements. Fortunately, the Obergefreiter Klaus Müller, in charge of reception, hates French pastries. He directly distributes the cakes to his men without touching it.

Accidental discovery

Corporal Heinrich Weber bites in his cake and finds ... a small roll of paper! But Heinrich, a former Bavarian baker, thinks it's a French secret recipe. He tries to decipher what he believes to be pastry instructions: "convoy 47 units direction Hendaye 0400H" becomes for him "47 eggs towards Four 4 am".

Culinary irony

Weber is so convinced that we discovered the secret of the Basque cake that he keeps all the messages found. He even writes to his wife in Germany: "I have pierced the mystery of French pastry, I will bring you the recipe!"

The real danger

The problem arises three weeks later when Hauptmann Dietrich, cultivated French speaking officer, falls on the "collection" of Weber. He immediately understands that these are not recipes ...

Miraculous leakage

Fortunately, Pantxoa had friends everywhere. Marie Etchegaray, who was cleaning up with the Germans, surprises a conversation and warns. When the Gestapo arrives at pastry the next morning, they only find an innocent grandmother (Pantxoa's mother) who claims that her son "left to sell his cakes to the Bayonne market".

The tasty epilogue

Pantxoa succeeds in going to Spain. After the war, he learned that Weber had tried to reproduce "his" secret recipe with the decoded false ingredients. His wife in Bavaria had received an enthusiastic letter: "Darling, I made the French cake with 47 eggs! It was an internetable but what an experience!"

Family legend

Even today, the Etcheverry family tells this story. Pastry still exists, and when German tourists ask for the "secret recipe", the current owners respond with a smile: "She is in the cake, you just have to know how to look for it!"

This authentic anecdote perfectly illustrates how a simple delivery error could have turned to drama, saved by cultural and culinary misunderstanding!

How to recognize a quality Basque cake:

He deserves that we know how to distinguish it in his most authentic version. Here is a detailed analysis of the essential criteria to recognize an excellent Basque cake.

History and provenance

A good Basque cake often has a story behind him. The best copies come:

- pastries established in the Basque Country for several generations

- of family recipes transmitted from generation to generation

- craftsmen who respect traditional methods

When an individual offers your family Basque cake, find out about the history of this recipe - family secrets often add this inimitable touch.

Visual appearance

A quality cake is first recognized by the eye:

- a beautiful golden color uniform, never dull or pale

- traditional patterns drawn on top (Basque cross or geometric patterns)

- a round and slightly curved, regular shape

- a beautiful shine that testifies to a beautiful gilding with the egg

The textures in perfect balance

The magic of an excellent Basque cake lies in the harmony of textures:

- a crisp exterior crust that offers slight resistance to the first bite

- a melting heart that contrasts with the outside

- a soft paste but which retains character

- No feeling of heaviness or excess of fat

Authentic flavors

The taste is obviously decisive:

- A good taste of butter that testifies to the use of quality ingredients

- Depending on the version:

- a well -scented pastry cream (often vanilla or sometimes rum) that does not stick to the palace

- or a jam of quality black cherries, tasty and not too sweet, ideally prepared with local cherries from ITXASSOU

The ultimate test

The most revealing criterion often remains this one: do you want to take a second piece immediately after having finished the first? An exceptional Basque cake always invites you to prolong the pleasure, a sign that the balance between all the elements is perfectly mastered.

To conclude, a real quality Basque cake is much more than a simple pastry -is a cultural heritage which, when prepared with replacement know -how, incomparable where tradition and excellence meet in

Preserve the inheritance of the Basque cake

Faced with these threats, several initiatives have emerged to preserve this invaluable heritage. The association of friends of the Basque cake has been working for years for the recognition and protection of the traditional recipe. Specific training is offered to young pastry chefs to ensure the transmission of authentic techniques. Some craftsmen have also taken steps to obtain a protected geographical indication (IGP), which would guarantee the origin and the methods of making the real Basque cake, a qualitative brand is not enough.

The safeguarding of this gastronomic know-how also involves consumer education, who must learn to recognize and enhance authenticity. By choosing the artisanal Basque cake rather than its industrial imitations, everyone contributes to the preservation of a living heritage and the sustainability of a tradition which continues to enrich our present.

The Basque cake reminds us that gastronomy is much more than a matter of taste - it is a reflection of a cultural identity, a collective history and a particular relationship to the world. Its preservation is an issue that concerns us all, temporary guards of an inheritance that we must transmit to future generations.

This emblematic dessert, at the crossroads between pie and cake, represents much more than a simple pastry-it embodies the soul of a territory, the history of a people and an ancestral know-how which has crossed the centuries. Bearer of an exceptional culinary tradition, the Basque cake illustrates perfectly what the backup can mean or, conversely, the loss of a gastronomic heritage.

Looking for the Basque cake: a quest for flavors and stories

For many years, I led a real quest around the Basque cake. It was not only the recipe that I was looking for, but the family stories that hide behind each variant of this emblematic dessert of the Basque Country.

The doors have often remained closed. Some families jealously keep their culinary secrets transmitted from generation to generation. Professionals also sometimes prefer to keep their tips that make the difference between a good cake and an exceptional cake.

But perseverance always pays off! Little by little, doors opened. I was lucky enough to meet enthusiasts who agreed to share not only their recipes, but also the anecdotes that accompany them—how grandmother added a touch of rum to the cream, how a pastry chef adapted a family recipe for his business, or how some families have perpetuated unique variations for centuries. These encounters taught me that the real treasure is not only found in the exact proportions or preparation techniques, but in the human history that is passed down along with the recipe. Each Basque cake tells a story, that of an Etxe (house), a family, a village, a tradition, a transmission that endures over time.

This culinary and cultural adventure ultimately offered me much more than recipes: it allowed me to forge links with guardians of tradition who, by opening their doors to me, also opened their hearts and their stories to me. The Etxe (houses) in the Basque Country do not necessarily open at the first AGUR (hello).

The Basque cake has an appointment with the story.

Eugenie at the top of the rhune

In the morning mists that enveloped the Pyrenean foothills, a strange procession advanced on the first slopes of Ascain. In the center of this procession, carried on a carrier chair decorated with purple and gold velvet, held the Empress Eugénie de Montijo, her face of Spanish beauty framed by the Valenciennes lace of his Mantile. The robust Basque Montagnard, chosen for their strength and their loyalty, were advancing a guaranteed step despite the weight of their precious load. The Empress, although born in Spain, discovered these border lands with the wonder of a child. The winding path crossed the green meadows where the manech (sheep) with a black head, silent witnesses of this extraordinary scene paid peacefully. When the procession finally reached Sare, it was as if the whole village had adorned itself with its most beautiful attire. The white facades of the laborer houses, enhanced with blood red half -timbering, seemed to have been freshly repainted for the occasion. The population, usually reserved for visitors from Paris, had massaged on the village square, the population expressing a rarely manifested fervor. "Biba Inperatriza!" they cried in the Basque language, while the Txalapartaris struck their wooden instruments, creating rhythmic music that resonated between the mountains. The young girls in traditional costume threw flower petals on the passage of the august visitinger, who responded with graceful smiles and handies of the hand. The procession then continued its laborious ascent towards the summit of the Rhune, this sacred mountain which dominates the Basque country with its 905 meters above sea level. As the climb progressed, the landscape was revealed in all its splendor: the Atlantic Ocean sparkling in the distance, the Nivelle valley and, in clear weather, the sharp peaks of the Pyrenees. It was at the windy summit of the Rhune, between heaven and earth, that a modest but significant event occurred. An old woman with a wrinkled face like a winter apple advanced towards the Empress, carrying in her callous hands a round cake with a golden crust. "For Your Majesty," she said simply, "" Hau Bixkotxa Egin Dizut, Gure Baseriko Produktuak, "she said in her millennial language, the guttural sounds sounding strangely in the rarefied air of the summit. An interpreter immediately translated into the Empress:" I made this traditional cake with the products of our farm. " The Empress, still moved by the grandiose panorama that was offered to her, accepted this present with gratitude. Was many of their Parisian pastry chefs. That of the Basque mountains. what is certain is that that day, at the top of the rhune where the sky seems to touch the earth, a simple pastry became the symbol of a link between a people proud of its traditions and a sovereign sensitive to local customs - a moment of grace in the great history of the Empire.

The Basque cake meets with Napoleon I.

Source: Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions in Paris.

Emperor Napoleon I arrived in Bayonne on the evening of April 14, 1808, accompanied by Empress Joséphine. They stayed there until July 21, 1808, residing at the Château de Marracq, where large diplomatic negotiations took place. A few days after their installation, the city's pastry chefs, anxious to mark this exceptional event, carefully presented a traditional Basque cake which they offered to the imperial table. This local specialty, as simple as it is elegant, was served at an official dinner attended by several dignitaries and Marshal Soult. The emperor, generally not very expansive on the pleasures of the table, was clearly surprised by this pastry. After having tasted it, he rested his fork for a moment and, turning to Marshal Soult, declared with unusual sincerity: "If I had to make my last breath at a table, it would undoubtedly be with a Basque cake in front of me. This remark, pronounced before witnesses, was quickly reported in the city. The Bayonnais pastry chefs, honored by this imperial recognition, received several orders from the castle during the rest of the Napoleon stay. This episode, although modest in the context of the major political events which then took place, contributed to the fame of the Basque cake and was part of local memory as a moment when regional gastronomy received the honors of the Empire.

Victor Hugo in Pasaia (1843). Between Basque Light and Shadow of Destiny

In August 1843, Victor Hugo stayed a few days in Pasaia, the small port nestled between the cliffs of the southern Basque Country, which we call the fjord. He finds an unexpected decor there: houses hanging above the water, the slow-going and the back of the boats, on the path of Compostela and a inhabited silence. Ily finds a home just in front of the last home of La Fayette who left for the Americas as a liberator. The place immediately inspires him. He writes, draws, dreams. It's a suspended moment. “Pasaia is a delight. »»

In this peaceful stop, he tastes local gastronomy - and discovers the Basque cake, a rustic specialty, made of golden dough and a heart of cream or black cherry.

But to everyone's surprise, he hardly appreciates. Too rich, too sweet for his Normand palace.

He says a word in his notebooks. This silence, in Hugo, is sometimes more than a thousand criticism.

A few days later, the news fell: her daughter Léopoldine died drowned, at the age of twenty.

Pasaia then becomes the last place of light before the tragedy.

And this cake, which he did not like, remains in history as a discreet symbol of this strange parenthesis where life still seemed soft.

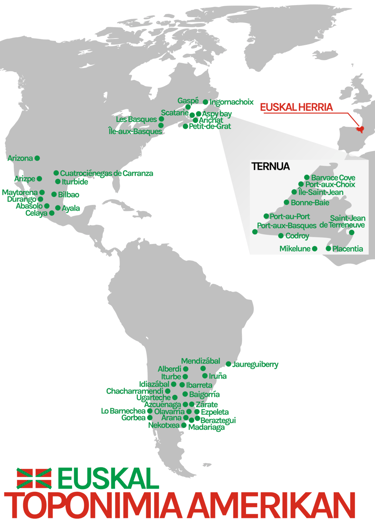

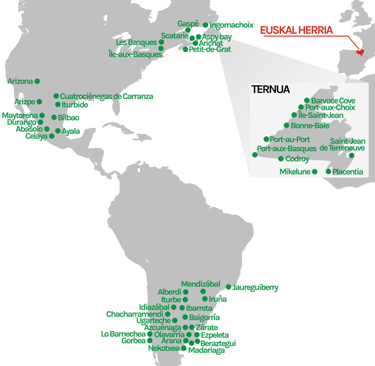

Basque sailors in all that: survival and traditions on the high seas

From the 16th century , the Basque sailors were among the most active in the North Atlantic. Originally from Ports like Pasaia, Donibane Lohizune or Ciboure, they participated in cod fishing on the Newfoundland benches and hunting for whales to the borders of the Labrador. These long maritime campaigns, sometimes several months, required a rigorous logistics organization, especially in terms of food.

Among the on -board provisions were biskotxas, dry cookies based on dough close to that used for the Basque cake. Their low humidity allowed them to keep permanently, even in a wet environment. More nourishing and tasty than ordinary sea pancakes, they brought additional comfort to seafarers at sea.

Another notable particularity: the Basques embarked cider, a fermented drink of abundant apples in their region. However, this cider, naturally rich in vitamin C, played a crucial role in scorbut prevention, a disease caused by this deficiency, which frequently decimated the crews of other nations. This habit, attested in several naval archives, partly explains the robustness of the Basque sailors and their longevity at sea.

The Albaola association, in Pasaia, works today in the reconstruction of traditional ships such as the whale San Juan (found off the Labrador) highlights this exceptional maritime heritage. Their work recalls that Basque sailors, in addition to being excellent browsers, were also precursors in the art of adapting to the sea, taking with them not only navigation tools, but also a culinary culture thought to last.

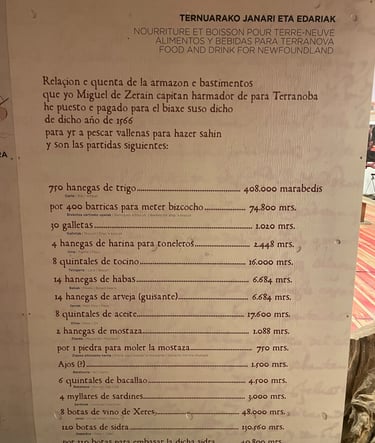

The "biscotx": the Basque cake goes to sea (16th-18th centuries)

Albaola documents reveal an unknown part of the history of the Basque cake: its transformation into travel provisions for the Basque whalers and moruutiers who crossed the Atlantic to Newfoundland.

Maritime genesis

In the 16th century, Basque sailors left for campaigns of 6 to 8 months. They needed foods that keep perfectly in the humidity of the holds and resist storms. The dough of the Basque cake, rich in butter and cooked until it becomes very firm, was ideal.

Technical transformation

The "biscotxak" (sea cookies) were prepared with the same dough as the traditional Basque cake, but:

- Kneaded longer to make it dense

- cooked twice (like Reims cookies) to eliminate all humidity

- Shape in flat and thick pancakes, more practical to store

- Without a garnish, which would have rotten

Conservation secrets

Port bakers like Pasaia, Saint-Jean-de-Luz or Ciboure had developed special techniques:

- prolonged cooking in wood ovens until you get a very hard crust

- Storage in waterproof barrels with layers of salt

- sometimes coated with beeswax for additional protection

Life on board

These cookies, hard as of stone, were soaked in boiled seafood, cider or wine to soften them. The sailors nicknamed them "tooth break" but they were vital: rich in calories, they gave the energy necessary for harsh maneuvers.

Culinary inheritance

When the ships returned to the port, families sometimes recovered unused cookies. They rehydrated them in hot milk with honey, creating a kind of nourishing porridge - distant ancestor of our puddings.

Archaeological proof

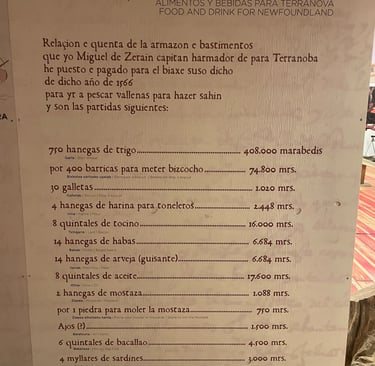

The Albaola shipyard, which rebuilds historical Basque ships, has found these livelihood lists in the archives in which these "400 barricas para meter bizcocho" (400 tons to store cookies).

Influence on modern pastry

This maritime tradition explains why the Basque cake dough is naturally more resistant and dense than other regional pastries. Conservation techniques developed for the sea have shaped the earthly recipe.

Thus, each Basque cake carries in him the soul of the great navigators who have traveled the oceans with, in their wedges, this precious dough which linked them to their native land.

The Basque cake a travel cake

The case of the pastry black false cherry

which uses artificially tinged supermarket cherries. The color detects on the dough, creating purple cakes. Trial with local producers!

The Sagardia affair: The Frelated Cherry Scandal (1987-1988)

The case broke out in September 1987 when Mikel Sagardia, a famous pastry chef of Hasparren, began to use importation cherries artificially tinged to replace the traditional black cherries of Itxassou, which has become too expensive after a bad harvest.

The first suspicions

it all starts with an innocuous observation of Maite Etcheberri, retired teacher and a fine connoisseur: "Your cakes spot your fingers, this is not normal." Indeed, the E124 (red cochenille) dye used to darken ordinary cherries detected on the dough, creating pinkish halos around the fruits.

The investigation in Itxassou

Pierre Haritschelhar, president of the ITXASSSOU Cherry Producers Union, conducts his own investigation. He buys incognito several cakes at Sagardia and had them analyzed by a laboratory in Pau. Result: traces of artificial colors prohibited in the name "black cherries of Itxassou".

The trap set

in March 1988, Haritscherhar organized a blind test during the Hasparren fair. He presents side cakes with real cherries by Itxassou and those of Sagardia. Experienced tasters immediately notice the difference: blatant taste, artificial color, and especially this tendency to rub off.

The public confrontation

The confrontation takes place in front of the town hall of Hasparren. Sagardia, trapped, tries to justify themselves: "Customers want reasonable prices, the real cherries of ITXASSOU cost three times more!" But his defense collapses when we discover that he sold his cakes at the same price by pretending to use the real cherries.

The consequences

- Boycott organized by local producers

- loss of 60% of its customers in six months

- obligation to reimburse the deceived customers

- prohibition to use the mention "Cerises d'Itxassou" for two years

the irony of Sagardia history

, in financial difficulty, must sell his pastry ... to his former apprentice who, for his part, only uses authentic cherries. Customers gradually returns, but the case has a long time marks the profession.

The inheritance

This affair pushes the producers of ITXASSOU to create in 1989 an AOC (appellation of controlled origin) for their cherries, the first step towards the current protection of their products. It also aware of consumers about the importance of the authenticity of traditional ingredients.

Even today, the former Hasparren tell the story of "Sagardia Eta Bere Gezurrezko Gerezi Beltzak" (Sagardia and its false black cherries), which has become an example of what should not be done in traditional Basque pastry.

The Jean-Baptiste Etcheverry affair, the pastry spy of Ciboure (1943-1944)

Jean-Baptiste, nicknamed "Pantxoa" , held family pastry against the port of Ciboure. Resistant in the "comet" network, he had found an ingenious system: slide coded messages in his Basque cakes by replacing part of the cream with fine papers rolled in beeswax.

The perfect system

The cakes were delivered to specific "customers" - in reality liaison agents. The code was simple:

- Normal grid = message inside

- Grock with diagonal scratch = no message

- Double gilding = urgent message

The fatal blunder of November 23, 1943

That day, Pantxoa is preparing two lots: "normal" cakes for the Germans of the Fort de Socoa (usual order on Thursday), and "coded" cakes for the network. In its precipitation - Aerial alert - it mixes controls.

The German -speaking miracle

The messages contained information on troop movements. Fortunately, the Obergefreiter Klaus Müller, in charge of reception, hates French pastries. He directly distributes the cakes to his men without touching it.

Accidental discovery

Corporal Heinrich Weber bites in his cake and finds ... a small roll of paper! But Heinrich, a former Bavarian baker, thinks it's a French secret recipe. He tries to decipher what he believes to be pastry instructions: "convoy 47 units direction Hendaye 0400H" becomes for him "47 eggs towards Four 4 am".

Culinary irony

Weber is so convinced that we discovered the secret of the Basque cake that he keeps all the messages found. He even writes to his wife in Germany: "I have pierced the mystery of French pastry, I will bring you the recipe"!

The real danger

The problem arises three weeks later when Hauptmann Dietrich, cultivated French speaking officer, falls on the "collection" of Weber. He immediately understands that these are not recipes ...

Miraculous leakage

Fortunately, Pantxoa had friends everywhere. Marie Etchegaray, who was cleaning up with the Germans, surprises a conversation and warns. When the Gestapo arrives at pastry the next morning, they only find an innocent grandmother (Pantxoa's mother) who claims that her son "left to sell his cakes to the Bayonne market".

The tasty epilogue

Pantxoa succeeds in going to Spain. After the war, he learned that Weber had tried to reproduce "his" secret recipe with the decoded false ingredients. His wife in Bavaria had received an enthusiastic letter: "Darling, I made the French cake with 47 eggs! It was an internetable but what an experience!"

Family legend

Even today, the Etcheverry family tells this story. Pastry still exists, and when German tourists ask for the "secret recipe", the current owners respond with a smile: "She is in the cake, you just have to know how to look for it!"

This authentic anecdote perfectly illustrates how a simple delivery error could have turned to drama, saved by cultural and culinary misunderstanding!

Discover the authenticity of the Basque cake.

Gourmet tradition and heritage

+33 6 08 48 09 85

© 2025. All Rights Reserved.